Summary

-

St. Elmo’s Fire

captures the struggles of young adults navigating adulthood in Reagan’s America, highlighting the excesses and anxieties of the era. - The characters reflect societal expectations of wealth, politics, and identity, illustrating the challenges of growing up in a changing world.

- Critics may dislike the characters’ privileged whining, but the film’s portrayal of post-college uncertainties resonates with themes of generational transition.

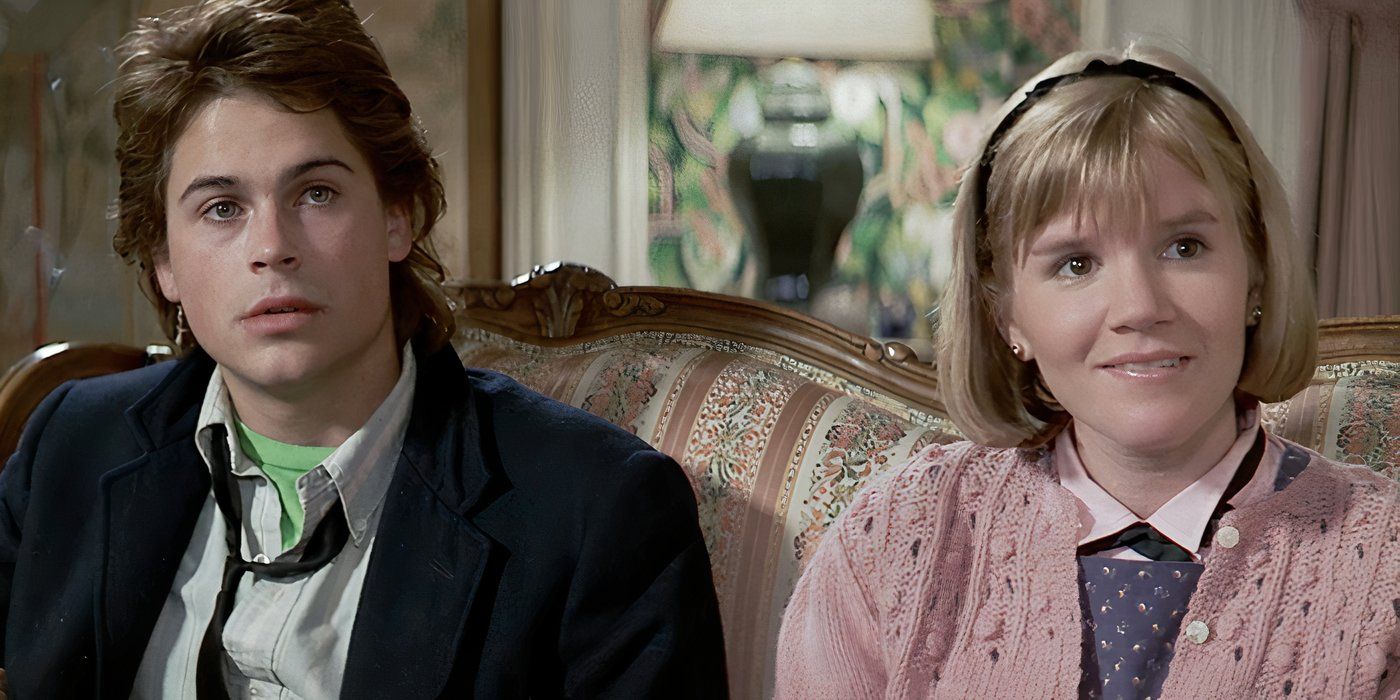

The 1985 Brat Pack-led drama St. Elmo’s Fire was far from a hit with critics, but the Joel Schumacher film captures a rarely examined aspect of growing up and coming of age amid Reagan’s America. Since the release of Andrew McCarthy’s Brat Pack documentary Brats, there has been renewed interest in revisiting St. Elmo’s Fire. The movie topped streaming charts, and there’s some buzz about a potential St. Elmo’s Fire sequel.

Yet, if Letterboxd reviews are anything to go by, modern audiences still struggle with the film’s deeply unlikable yuppy characters who whine about their privileged lives. These criticisms of St. Elmo’s Fire are valid; they are terrible people who make terrible decisions. On the surface, St. Elmo’s Fire’s friend group seems like poorly drawn characters, and I can understand why audiences respond negatively to their seemingly willful naivety. But I think this was a deliberate choice by Schumacher and co-writer Carl Kurlander. Dismissing the iconic Brat Pack classic based on these complaints completely misses the film’s point and historical context.

Related

St Elmo’s Fire Cast: Where Are They Now?

St. Elmo’s Fire is one of the movies that helped cement the Brat Pack, but the actors have all moved on from teen roles since the 1980s.

St. Elmo’s Fire In Reagan’s America

St. Elmo’s Fire Was A Reaction To Living With Reagan-Era Politics

St. Elmo’s Fire came out at the peak of Reaganism in America, with widening economic inequality, an increasing intensification of Cold War military action against the Soviet Union, and a raging AIDS epidemic. It was a time when rampant Reaganomics reigned. Like the seven friends at the center of St. Elmo’s Fire, young people were navigating their way through the anxiety and paranoia of the day.

Ronald Reagan served as President of the United States from 1981 to 1989. During his tenure, Reagan adopted sweeping new neoliberal policies that were collectively known as Reaganomics or Reaganism. Some argue his policies led to a stronger GDP and a boom in entrepreneurship, while others suggest Reagan’s policies caused increased income inequality, tripled national debt, and fostered an atmosphere of greed.

The characters were also facing the era’s excesses, consumerism, and the irresistible allure of wealth that Reagonomics promised. The contrasting approaches to this are most clearly seen in Jules Van Patten (Demi Moore) and Wendy Beamish (Mare Winningham). Jules will do anything to prove her worth by overtly flaunting her flashy clothes and jewelry. Moore’s character is sucked into the world of excessive consumerism, believing that the outward appearance of success and wealth will lead to power and happiness, but it ultimately destroys her.

Whereas Wendy comes from family wealth but refuses to display her wealth. She wears dowdy outfits and is embarrassed by anything that betrays her as anything above the middle class. Instead, Wendy strives to prove her worth through social work and wants to define herself outside the context of money. However, Wendy still struggles to escape the trappings of her affluence, often running back to daddy for a handout when she needs extra cash.

St. Elmo’s Fire Exposes The Problems With College

The Characters Are Ill-Equipped To Live With AdultResponsibilities

St. Elmo’s Fire captures a snapshot of a specific and challenging time in young people’s lives as they graduate from a life of regulation and routine at school and into the world of adult responsibilities and consequences. In many ways, the Brat Pack film is as much an indictment of the way universities fail to prepare young people for these changes than anything else.

For young adults transitioning from the comfortable cushion of college life and into the responsibilities of adulthood, the new world would’ve looked markedly different from what they’d been exposed to at school. While the seven friends all graduate, they seem ill-equipped to manage life in the real world. This sets up the characters to fumble through life, making terrible mistakes and not being clear about where they fit. The characters, once united in the camaraderie of college life, now must navigate a world driven by excess, greed, and individualism.

Rob Lowe’s character, Billy Hicks is the least prepared for these life changes. He can’t get past his frat boy lifestyle despite being a husband and father. He’s lost in a world of adults and sees his friends making grown-up decisions at jobs, but he just can’t – or doesn’t want to – get his life together. Desperate, Billy returns to the frat house where he had clout and had found meaning while at school. But here, he finds he has no legacy, and the new cohort of frat boys only sees him as a guy who can score drugs for them.

Identity, Money, And Politics In St. Elmo’s Fire

The Characters Create Identities As A Reflection Of The Excesses Of The ’80s

Within the context of mid-’80s extravagance, St. Elmo’s Fire paints characters representing binaries of wealth, and politics that became central to forming identities. The world expected these young people to choose a track that would define them for the rest of their lives, and money and politics were at the core of these binary forms of identity. I think Schumacher and Kurlander chose these elements deliberately, as they were central topics amid Reagan’s America in the early to mid-’80s.

Jules and Wendy are clearly defined by their wealth and their identities are entwined within it. Likewise, Alec Newberry (Judd Nelson) sees politics as both an identity and a path to wealth accumulation. Alec was the President of the Young Democrats while at Georgetown, but he abandons his beliefs for the promise of “moving up” in pursuit of wealth and power. He’s molding an identity that he thinks the world expects of him, and as a chronically unfaithful boyfriend who repeatedly proposes to Leslie Hunter (Ally Sheedy), he sees his decisions as ones necessary for growing up.

Ultimately, St. Elmo’s Fire chronicles a moment in early adulthood rarely addressed in cinema. It’s messy, and the characters’ transition into the real world within the excesses of Reagan’s America captures this feeling of uncertainty and being lost. For those emerging from university in the heady mid-80s, amid changing social and economic values and rising consumerism, individualism, and fear, St. Elmo’s Fire keenly encapsulates a period of history, presenting themes that resonate through time. All the hate for this Brat Pack classic just misses the point of the film and what it was meant to represent.